by Kim Fitzsimmons, The Connecticut Post, Bridgeport, Connecticut

Published 2/25/00

Return to Gwyneth Walker Home Page

Return to Gwyneth Walker Music Catalog

Return to Gwyneth Walker Recordings Page

Read notes for Concert Suite (1994) for orchestra

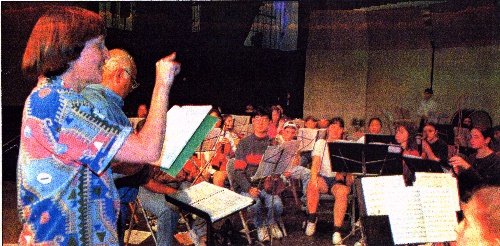

(Photograph of Gwyneth Walker, Robert Genualdi and the Greater Bridgeport Symphony Youth Orchestra.)

For those who equate classical music with long-gone men, the name Gwyneth Walker might not ring a bell.

But years from now, that may well change. Walker is already a figure of note among those familiar with contemporary American music. She considers her fame an unexpected distinction.

"I wouldn't have believed, when I was young and starting out, that people would be playing my music around the world every single day. But as we speak, someone, somewhere in the world, is," says Walker who has homes in New Canaan (Ct.) and Vermont.

"When musicians from this country go abroad and want to play American music, they often pick mine."

Walker, 48, who has written more than 90 commissioned works for orchestra, band, chorus and chamber ensembles, is a rarity among composers in supporting herself entirely with her writing.

"She is a bona fide legitimate composer with a lot of published music, one of the young American composers of importance," observed Robert Genualdi of Weston, former Fairfield High School headmaster and music director for the Greater Bridgeport Symphony Youth Orchestra. "She is one of the outstanding composers in Connecticut."

Students in several schools in the region are about to become more familiar with Walker and her work as she conducts a series of classroom programs on contemporary composition this week, in connection with the premiere performance of a commissioned work by the GBSYO's principal orchestra on Saturday at Fairfield High School.

Walker, a former college professor (advanced theory and composition), will tailor her presentation to a younger crowd as she talks with the groups of elementary and high school students in Fairfield, Bridgeport and Monroe.

"This is a chance for these kinds to meet a live composer, to get a sense of the musical experience," said Beth Harris of Fairfield, a parent who has been active in promotion the youth orchestras and related activities. "Many of these kinds would never have had the opportunity to do this. Not only will she do a presentation, she'll also talk with the kids. It's a way for the music they hear to come to life."

Walker will begin the program by playing taped samples of her work or will have live musicians perform it. Then she will describe the day-to-day life of a composer, from the creative process to the business end.

Students, she said, need not be musically inclined. "Simply talking with someone who creates anything (stories, paintings, music) as a daily lifestyle is of great interest to them ... They always ask me how much money I make and if I am married with children [she is not], all of which I answer openly and with respect for their questions."

One of the more common questions usually revolves around Walker's beginnings: who and what influenced her, how she got started.

The latter did not occur as one might expect, with formal lessons and rigorous training, but on a far more casual basis, she said.

"I really started when I was 2; we had a piano in the house and my older sister was taking lessons. I remember listening to her play one night after I went to bed, and was just fascinated by what I had heard. The next morning I crawled toward the piano and started making up sounds. I emulated by ear the progressions."

Eventually Walker did receive formal training, majoring in music composition at Brown, with graduate studies at the Hartt School of Music in Hartford, but parental pressure to suceed here was minimal.

"I also played a lot of tournament tennis and was successful at that, and was always building things, too. An inventive person is sometimes inventive in many spheres, so my parents' approach was always 'That's nice, dear.' They just expected me to succeed at whatever I did -- today a symphony, tomorrow a fort in the back yard."

Walker's friends and colleagues, on the other hand, were far more demanding, driving her to produce. "The world doesn't always welcome new composers, but if people are always asking you for things, and enjoying it, it gives you the basis to go on. The constant involvement has helped me to grow, and I can't imagine life without writing music."

Not that it's always easy; the creative process is a constant challenge, particularly in terms of expressing coherent emotions and ideas. "You can't just ramble on. It may be interesting to you, but it's not to the listener."

Though Walker has studied the works of countless composers, particularly in terms of shape and form, she says there is no one significant influence, no one whose work is reflected in her own. She is partial to folk music and jazz, and to the works of 20th century composers Benjamin Britten and Samuel Barber, but, she said, "I sound like myself."

Genualdi, who conducts the principal orchestra (there are two others as well -- string and concert), said he had suggested commissioning Walker because of her standing in the music community, and because of the opportunity it affords orchestra members.

"It's a rare thing for young people to give a musical composition its world premiere. We're going to be the first ones to play it, and have had the opportunity to interact with the composer. It's a unique thing -- a real live 20th century composer."